🖊 This article was last updated on October 3, 2019

Introduction

You can’t change what you’re not aware of.

The same thing goes with shifting habits: Understanding how habits are formed allows us to work with our biology to create positive routines.

As you read Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, you’ll realize that you don’t have to exhaust your willpower to get things done. You can use your biology to automate good routines and override destructive habits.

Aside from staying on the New York Times best-seller list for two years, The Power of Habit was named one of the best books of the year by the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. Cartoonist and author Scott Adams also recommended the book in his Persuasion Reading List.

Below is a quick summary of The Power of Habit, as well as my key takeaways and favorite quotes. I hope these inspire you to leverage the habit loop to fuel your personal and entrepreneurial success.

The Golden Rule of Habit Change: You can’t extinguish a bad habit, you can only change it.

Charles Duhigg

Book Chapters

The book is divided into three parts: the habits of individuals, organizations, and societies. One thing I loved about this book is it starts off with the basics–a research-backed understanding of why and how our brains form habits. From here, Duhigg discusses strategies we can easily use to create or change our habits.

Part 1: The Habits of Individuals

- The Habit Loop: How Habits Work

- The Craving Brain: How to Create New Habits

- The Golden Rule of Habit Change: Why Transformation Occurs

Part 2: The Habits of Succesful Organizations

- Keystone Habits, or the Ballad of Paul O’Neill: Which Habits Matter Most

- Starbucks and the Habit of Success: When Willpower Becomes Automatic

- The Power of a Crisis: How Leaders Create Habits Through Accident and Design

- How Target Knows What You Want Before You Do: When Companies Predict (and Manipulate) Habits

Part 3: The Habits of Societies

- Saddleback Church and the Montgomery Bus Boycott: How Movements Happen

- The Neurology of Free Will: Are We Responsible for Our Habits?

The Power of Habit Summary

Part 1: Individual Habits

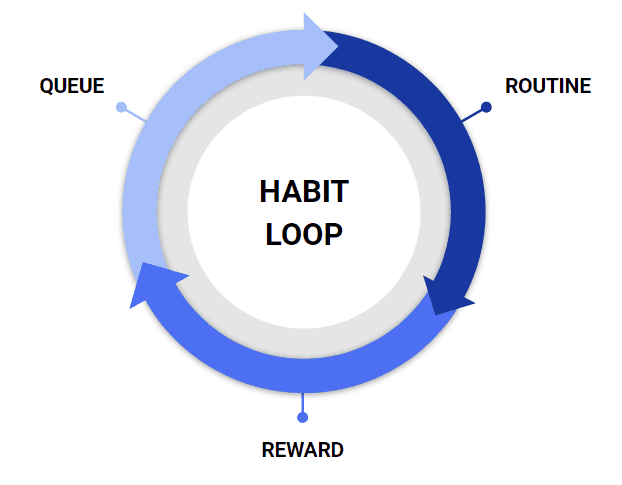

According to scientists, our habits are made up of three parts–the cue, routine, and reward. This is the habit loop. Each part plays a critical role: the cue serves as the trigger, telling the brain what action to take. Then there’s the routine, which is the action or behavior we take. Lastly, rewards refer to the pleasure we feel after doing our routine.

This process of turning a set of actions into a habit is called chunking. A part of our brain–the basal ganglia–stores these patterns, so they run automatically with little brain effort. With these habits in place, we no longer have to think about our every move.

Now we know why we can, almost without thinking, drive back home, brush our teeth, or make our coffee, even as a million things are running through our head.

But there’s a key ingredient that cements a habit, which Duhigg discusses in chapter 2: cravings. Once we get a cue, our brains automatically crave the reward.

This has some biological significance. Getting a reward at the end of your routine tells the brain the action is worth repeating. But if the reward is removed, that tells our brain it might not be worth doing again.

So if we want to change a habit, it’s important to create a craving, or at least to mentally crave the reward.

Duhigg follows this with “The Golden Rule of Habit Change” in Chapter 3. We all know that getting rid of an old, deeply ingrained habit is pretty hard for anyone. If we want to change a habit, we need to shift only the routine, and retain the same cue and reward. And just as important, we’ve got to believe that change is possible.

Let’s say for example when your alarm goes off at 6 a.m. (cue), you just roll in bed and stay for another half hour (routine), before getting up to make your coffee (reward). If you want to include exercise into your day, you need not change the cue (alarm) and the reward (coffee), but only the routine. Instead of rolling in bed, you get up and run around the block, all the while thinking of your favorite cup of coffee.

Part 2: The Habits of Succesful Organizations

Part 2 talks about organization habits, citing a few studies plus examples from organizations such as Alcoa (Aluminum Company of America), Starbucks, and Target.

In Chapter 4, Duhigg introduces keystone habits–those habits that have a domino effect. In a weight loss study, keeping a food journal helped obese participants track times when they eat unhealthy snacks. They then used these insights to plan healthier meals. Eventually, those who maintained their food journals lost more weight than the control group.

Chapter 5 talks about willpower. Willpower can be developed, but like our muscles, willpower can be depleted. To build willpower, it is important to identify or anticipate the most painful points, and then have a plan how to beat these.

In the case of Starbucks, managers trained their baristas how to handle stressful situations. When the baristas finally had to deal with an angry customer, the LATTE routine (listen to customer – acknowledge the complaint – take action by solving the problem – thank the customer – explain why the problem occurred) automatically kicked in.

If you want to do something that requires willpower—like going for a run after work—you have to conserve your willpower muscle during the day.

Charles Duhigg

In Chapter 6, Duhigg shows how habits can be used to maintain peace in organizations, from avoiding turf battles to managing internal conflicts. Duhigg also cites examples of how crises revealed gaps in companies’ systems, and led to important changes in company policies.

At the end of Part 2, Duhigg discusses how companies predict and manipulate consumers’ habits (Chapter 7). Companies often leverage psychology to increase sales–from the way goods are arranged in supermarkets, to customizing deals sent to customers based on their purchase history.

Companies can target customers subtly by inserting the new deal (such as baby items if they think you are pregnant) in between coupons for familiar items such as soap. This strategy illustrates the concept Duhigg explains in chapter 3, on how old cues can lead to new routines.

Part 3: The Habits of Societies

In Part 3 of the book, Duhigg discusses habits of societies, touching on how social movements lead to change, beginning with close friendships and the habit of helping friends, until the cause spreads beyond the inner circle.

Lastly, he talks about the neurology of free will in Chapter 9, which poses a question: Are we morally responsible for our habits?

Duhigg cites the case of a man suffering from sleep terror when he killed his wife, and a woman who got into debt due to her gambling addiction.

The man who killed his wife in his sleep could not be held accountable for his action, because he was not conscious nor could he anticipate when the sleep terror would happen. The gambling addict, on the other hand, was aware of her behavior and did not take sufficient steps to curb her addiction.

My Key Takeaways

- Changing a habit doesn’t have to be a Herculean task. We start with what we already have: a cue and a reward, and only shift the routine.

- To fuel a new habit, we need to identify our cravings, and leverage those. For example, if we want to start using the Pomodoro technique to be more productive, and we love watching YouTube videos, we can use the videos as our reward.

- Though keystone habits and willpower are discussed under organizational habits, these concepts are useful for our individual habits too. Instead of overhauling our routines, we can start identifying a keystone habit–a small win–that can lead to a series of simple victories in our lives. It can be as simple as keeping a daily gratitude journal, parking further from our office to force ourselves to exercise a bit, or keeping our phones on silent mode while we work.

We can identify our pain points ahead of time–the difficulties we’d encounter, the things that may keep us from following through–and have a plan for addressing those.

Habits can be changed, if we understand how they work.

Charles Duhigg

Who’s It for

Anyone struggling to change a bad habit or create a new one will appreciate this book. Knowing the biology behind our habits allows us to utilize our brain’s abilities to automate and incentivize positive routines.

Students, employees, solopreneurs, team leaders, and marketers can pick up new strategies from Duhigg’s book to better implement changes in their personal lives, and influence the habits of their subordinates and clients.

My 5 Favorite Quotes

This process within our brains is a three-step loop. First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.

When a habit emerges, the brain stops fully participating in decision making. It stops working so hard, or diverts focus to other tasks. So unless you deliberately fight a habit—unless you find new routines—the pattern will unfold automatically.

Want to exercise more? Choose a cue, such as going to the gym as soon as you wake up, and a reward, such as a smoothie after each workout. Then think about that smoothie, or about the endorphin rush you’ll feel. Allow yourself to anticipate the reward. Eventually, that craving will make it easier to push through the gym doors every day.

Keystone habits offer what is known within academic literature as ‘small wins.’ They help other habits to flourish by creating new structures, and they establish cultures where change becomes contagious.

This is how willpower becomes a habit: by choosing a certain behavior ahead of time, and then following that routine when an inflection point arrives.

- These Black Friday deals will skyrocket your productivity (2021 edition) - November 11, 2021

- How to Stay Productive as a Digital Nomad - December 23, 2019

- When is the right time to outsource? - December 3, 2019